Students learn how to doodle their way to better grades

They say a picture is worth a thousand words.

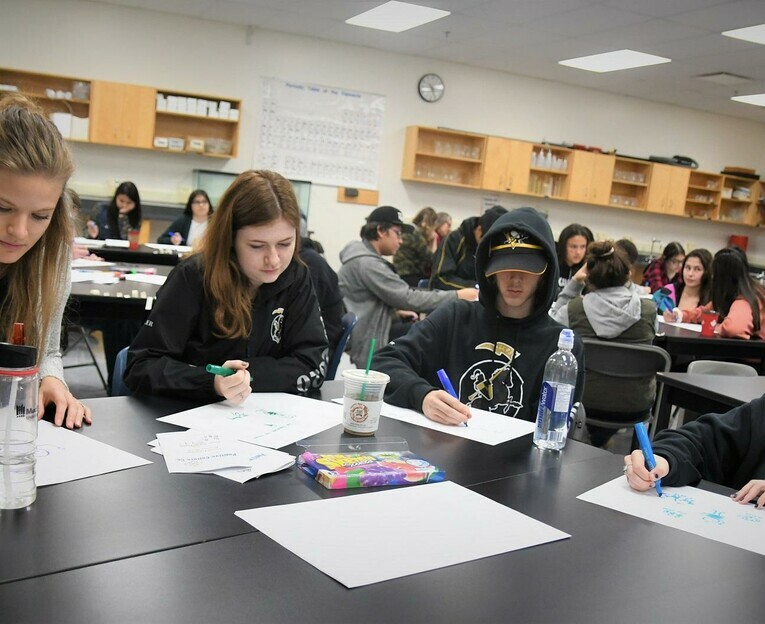

On Thursday, senior high students from across Fort Vermilion School Division had an opportunity to learn how to use their drawings as a way to access memories and improve learning, also known as “sketchnoting” – like note-taking with doodles instead of written lines.

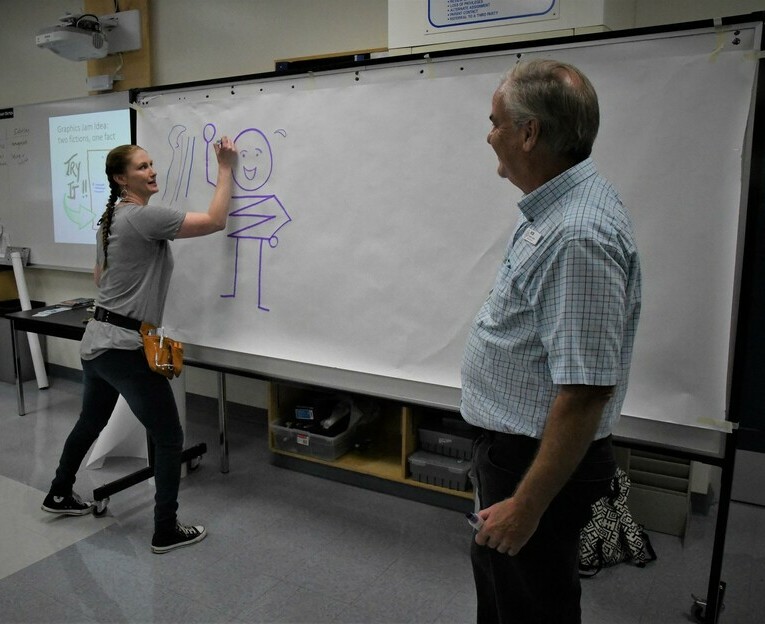

Father-daughter duo Robert Benn and Melanie David are visual practitioners who were in High Level Public School to teach visual language skills to students from HLPS, Fort Vermilion Public School, La Crete Public School, and Upper Hay River School.

The goal was to inspire the students to progress along their own visual language journey and learn how to create a personal “dictionary” of visual information they can use to communicate more clearly with themselves and with other people.

“We have to move out of the thinking that doodling while you are listening is a distraction,” said David. “Science has told us over and over that it is not a distraction. It enhances memory and focus.”

Instead of random doodling, David and Benn teach students to focus their drawing to associate with the topic they are taking notes on as a way of enhancing their learning ability.

“Parents whose children engage in this should see immediate improvements in test scores, test performance, and participation in classrooms,” David said.

“The really cool thing about it is the science has shown us it’s not the quality of the visual that makes the memory,” said Benn. “It is just the actual process of making the visual. Even if your horse doesn’t look like a horse, you will remember (details) about the horse when you are doodling.”

In fact, not only will students remember the horse, but they will remember the information they were learning around the horse. It’s a memory process Davis calls “chunking” and is a way in which our brains store information.

Phone numbers, for example, are often remembered in three “chunks” comprised of the area code (a chunk) followed by the first three digits (a chunk) and then the last four digits (another chunk). This allows us to remember an otherwise random set of 10 digits.

“We remember in patterns,” David said. “Visuals help us to be able to chunk information into usable, bite-sized pieces we can then take apart and analyze from there to understand more clearly.”

The process is so effective the students should be able to take the visuals they worked on in the course and use them to inform other students who were not present.

“Their memories of the details and conversations, and what was talked about and laughed about will be contained within those images that they remember producing today,” said David.

The key to success here, as it is in most things, is practice. Students need to realize and be comfortable with the fact this is a process, and when they start something new, they will not be an expert at it. It can be a little uneven at first as students become more comfortable using visual language. The more they practice, the more accessible the skill becomes.

“It can become fluid to the point where you come to a university lecture, listen to the lecturer speak, and pretty much draw a picture of the lecture rather than pages and pages of paragraphs of notes,” said David. “It’s a lot easier to go back to that to study from at a later date.”

“Visual language appeals to our more primitive brain structures,” she added. “The way humans have evolved since we were drawing on caves – (we have) the same brain we are using now as we were using back then. That brain was specifically cued to visual stimulus, and so is ours. A lot of our memory functions and a lot of the way we process the world is visual by nature.

“We are just glomming onto that natural tendency of our brain to feel comfortable with imagery.”